The Unique Architecture of Anglo-German Freemasonry

In the vast and intricate architecture of the United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE), where uniformity of ritual and adherence to established custom are often paramount, Pilgrim Lodge No. 238 stands as a singular anomaly. Consecrated in the late 18th century, deep within the Georgian era, it represents more than a mere administrative unit of the fraternity; it is a living historical artifact of Anglo-German relations, a theological bridge between the Christian chivalry of the Continental Enlightenment and the universalist deism of the British Craft, and a resilient survivor of the two greatest geopolitical catastrophes of the 20th century.

The history of Pilgrim Lodge is one of a microcosm of the German experience in London over the last two hundred and forty years. From the personal union of the British and Hanoverian crowns, which facilitated its founding in 1779, to the cosmopolitan optimism of the Edwardian era, and finally through the “darkness” of the World Wars where the lodge was silenced by anti-German sentiment, Pilgrim Lodge has served as a barometer for the integration and isolation of the German-speaking community in the British capital.

Distinguished by its unique warrant, Pilgrim Lodge holds the exclusive privilege under the English Constitution to work in the German language and to practice a ritual, the Schroeder Rite, that is fundamentally distinct from the Emulation, Stability, or Bristol workings found elsewhere in the British Isles. This short essay provides an exhaustive analysis of the lodge’s evolution, examining its transition from the Swedish-influenced Zinnendorf Rite to the humanist Schroeder Rite, its pivotal role in the formation of the Anglo-Foreign Lodges Association, and its enduring legacy as a sanctuary for the persecuted and a nexus of our brotherhood.

The Hanoverian Context and the Founding (1770-1800)

To understand the genesis of “Der Pilger,” one must first reconstruct the social atmosphere of London in the 1770s. The British monarchy was German. King George III, though the first of his line to be born in England and speak English as a first language, remained the Elector of Hanover. This personal union created a porous channel between the Thames and the Leine, facilitating a steady flow of diplomats, courtiers, soldiers, merchants, and artists between the German states and London. By 1779, London possessed a substantial, affluent, and politically connected German community. Many were officials of the King’s German Legion or the Hanoverian Chancery in London. They existed in a high-status enclave, integrated into the Court of St. James yet culturally distinct. It was within this specific milieu (aristocratic, mercantile, and deeply connected to the court) that the impulse to form a German-speaking lodge arose.

The central figure in the lodge’s creation was Johann Leonhardi. Historical records identify him as a founder but as the primary architect of the lodge’s existence. Leonhardi was a man of significant diplomatic weight, deeply embedded in the masonic networks of the Continent. In April 1777, he was dispatched to London, likely with a specific mandate to organize the German masonic diaspora.

By August 1779, Leonhardi had successfully navigated the bureaucracy of the Premier Grand Lodge of England (the “Moderns”). He obtained a Warrant to establish “Loge der Pilger” (The Pilgrim Lodge), originally numbered 516. This achievement was remarkable for two reasons. First, the Moderns were generally wary of the complex, high-degree systems proliferating on the Continent. Second, Leonhardi secured a special dispensation that was highly unusual for the time: the right to work in the German language and, crucially, to use “their own ritual”.

The status of the new lodge was immediately recognized as exceptional. On February 7, 1781, Johann Leonhardi was admitted to the Grand Lodge not as a rank-and-file master of a private lodge, but as the official representative of the National Grand Lodge of Germany. He was accorded a rank immediately following the Grand Officers, a protocol that signaled Pilgrim Lodge was to function as a quasi-embassy of German Freemasonry within the English jurisdiction. The composition of the early lodge reflected the stratification of the German community. The founders included men attached to the Hanoverian administration or the Royal Household, who provided the lodge with political cover and social prestige, but also the wealthy burghers of the City of London, whose trade links with Hamburg and Bremen were vital to the British economy. Figures like Rainsford and Woulfe, who were members of “Der Pilger” and were deeply involved in the transmission of esoteric knowledge, specifically regarding Swedish high degrees.

These men sought a space where the brotherly principles of masonry could be practiced in their mother tongue, free from the linguistic barriers of English lodges, and, more importantly, according to the specific ritualistic forms they held sacred.

The Era of the Zinnendorf Rite (1779-1852)

For the first seventy-three years of its existence, Pilgrim Lodge did not practice the universalist, deistic Freemasonry associated with the English Craft. Instead, it worked the Zinnendorf Ritual.

The choice of this ritual is critical to understanding the early character of the lodge. The Zinnendorf Rite was a system derived from the Swedish Rite, formulated in 1766 by Johann Wilhelm von Zinnendorf, the Grand Master of the Grand National Mother Lodge of the Three Globes in Berlin. Zinnendorf had been a member of the Strict Observance, a dominant European masonic order that claimed descent from the Knights Templar. When the Strict Observance began to fracture, Zinnendorf created his own system, heavily influenced by Swedish mysticism.

The Zinnendorf Rite was characterized by its explicit Christianity: it was not open to men of all faiths. It required a profession of Christian belief, specifically Trinitarianism. It was not limited to the three degrees of Apprentice, Fellowcraft, and Master Mason. It included higher grades that elaborated on Christian chivalry and Templar legends. The ritual was very ornate, designed to convey complex spiritual hierarchies rather than moral instruction.

The existence of a Zinnendorf lodge under the jurisdiction of the English “Moderns” is a historical paradox. The English Grand Lodge had moved toward religious tolerance and simplicity, while the Zinnendorf system was sectarian and elaborate. Yet, Pilgrim Lodge thrived. This was likely due to the personal influence of Leonhardi and the diplomatic utility of maintaining a link with the powerful Grand Lodges of Berlin and Sweden.

During this period, Pilgrim Lodge served as a conduit for esoteric information. The “Philaléthes”, a group of French esotericists, corresponded with members of Pilgrim Lodge like Rainsford to obtain information on the Swedish high degrees, noting that the material was partially censored because of Sweden’s stringent requirements of secrecy. This identifies Pilgrim Lodge as a hub of the Strict Observance network in London, a place where the Alchemical and Templar currents of the 18th century intersected with the rationalism of London society. The passage of the Union of 1813, which formed the United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE), marked the beginning of the end for the Zinnendorf era at Pilgrim Lodge. The Union defined “pure Antient Masonry” strictly as the three degrees (plus the Royal Arch). While Pilgrim Lodge retained its privileges, the intellectual climate of the 19th century was shifting. The “High Degree” systems, with their claims of Templar descent and occult secrets, were increasingly viewed with skepticism. The rise of historical criticism and the “democratization” of the Craft made the aristocratic and secretive Zinnendorf Rite seem like an anachronism.

The Great Reformation and The Adoption of the Schroeder Rite (1852)

By the 1840s, the Zinnendorf Ritual had become a liability. The Victorian era brought a new emphasis on universality. The explicitly Christian nature of the Zinnendorf Rite was no longer appropriate to the teachings of Freemasonry as they were understood in a liberalizing Britain. The lodge faced a dilemma: conform to the standard English Emulation ritual and lose its German identity, or find a new ritual that was compatible with English principles.

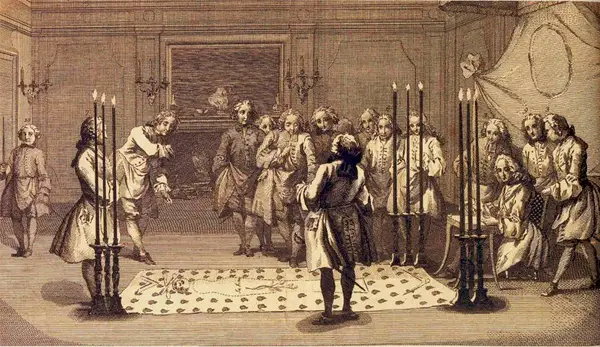

The solution lay in the work of Friedrich Ludwig Schroeder (1744-1816), depicted above. Although Schroeder had died decades before Pilgrim Lodge adopted his ritual, his legacy provided the perfect vehicle for the lodge’s transformation. Schroeder was a titan of the German stage, an actor, manager, and playwright in Hamburg who was instrumental in the Hamburg Dramaturgy and the promotion of Shakespeare in Germany. As a Freemason, Schroeder was a radical reformer. He was deeply critical of the Strict Observance and the “overloaded systems of higher degrees,” which he felt were cluttered with mysticism, alchemy and Rosicrucianism.

Schroeder’s goal was to strip away these accretions and return to the old customs of the English stone masons. He embarked on an intense research project, seeking the pure and unadulterated origin of the Craft. In a twist of historical irony, Schroeder erroneously believed that early English exposures or the books written to reveal masonic secrets to the public were actually authentic ritual texts. Specifically, he relied on Three Distinct Knocks (1760) and Masonry Dissected (1730). Schroeder believed Three Distinct Knocks was the older and more authentic text though modern scholarship knows it to be a later “Antients” exposure. He translated these English texts into German, filtered them through the humanist lens of Weimar Classicism, influenced by his friend Goethe, and created a ritual that was simple, dignified, and focused on moral education rather than alchemy.

In 1852, Pilgrim Lodge formally abandoned the Zinnendorf Rite and adopted the Schroeder Rite (Schrödersche Lehrart). This was a masterstroke of adaptation. By adopting Schroeder’s ritual, Pilgrim Lodge retained the German language and aligned with UGLE. The ritual was “highly humanitarian,” moving away from the sectarian Christian requirements of Zinnendorf. This decision created the unique situation that persists today: Pilgrim Lodge works a ritual that is structurally older than the standard English “Emulation” ritual standardized after 1813, preserving 18th-century English forms that have been lost in England but preserved in German translation.

The Victorian Zenith and the International Masonic Club (1860-1914)

Throughout the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, Pilgrim Lodge flourished as the premier social institution for German men in London. It attracted merchants, scientists, and intellectuals. A notable initiate from this period was Theodor Reuss, who was initiated on November 8, 1876, passed on May 8, 1877, and raised on January 9, 1878. While Reuss would later become infamous for founding the irregular Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.) and was eventually excluded from regular masonry, his early masonic career in Pilgrim Lodge demonstrates the lodge’s role as the primary gateway for German seekers in London.

By the turn of the 20th century, Pilgrim Lodge was no longer the sole foreign lodge in London. It had been joined by Loge La France No. 2060 (French) and Loggia Italia No. 2687 (Italian). In 1903, W.Bro. Major John W. Woodall, a Past Grand Treasurer of UGLE, convened a meeting with 16 brethren to discuss a grander vision: a club to “promote peace in the world through the Brotherhood of Freemasonry”. This initiative led to the founding of the International Masonic Club (IMC) in 1904. The club was established by four lodges:

- Pilgrim Lodge No. 238 (German)

- Loge La France No. 2060 (French)

- Loge L’Entente Cordiale No. 2796 (French)

- Loggia Italia No. 2687 (Italian).

The first meeting was held at the Cafe Royal on Regent Street on March 26, 1904. Pilgrim Lodge, as the senior lodge, took a leading role. The club prospered rapidly, growing to 200 members by 1910.

The zenith of Pilgrim Lodge’s pre-war influence occurred on March 10, 1910. The International Masonic Club held a massive meeting under the banner of Pilgrim Lodge. It was attended by the Pro Grand Master, Lord Ampthill, and over 500 members and visitors. The meeting was presided over by W.Bro. Oscar Guttman, the Master of Pilgrim Lodge. Guttman was a distinguished chemist and explosives expert, a figure of significant standing in the scientific community. His leadership of the meeting, alongside Frederick C. van Duzer of America Lodge, symbolized the height of cosmopolitan fraternity. Tragically, Guttman died later that same year in a motor car accident in Brussels, a loss that foreshadowed the greater tragedy to come.

Into the Abyss: The Dark Years (1914-1945)

The ideals and high hopes of the International Masonic Club were shattered with the outbreak of World War I in 1914. The position of a German-speaking society in London became precarious overnight. The anti-German hysteria in Britain was intense; shops were looted, and German cultural institutions were viewed as nests of spies. In this toxic environment, the brethren of Pilgrim Lodge faced an impossible situation. To continue meeting would have been seen as an act of defiance. Consequently, the two German-speaking lodges (Pilgrim and its younger counterparts) went into darkness. The meetings were suspended. The warrant was not surrendered, but the lodge ceased to labor. This suspension lasted for the duration of the war and well into the next decade, as the bitterness of the conflict made an immediate revival impossible.

It was not until 1927 that Pilgrim Lodge resumed its regular meetings. The revival was driven by the surviving members and the renewed spirit of the Anglo-Foreign Lodges Association. The meetings of the Association itself resumed in October 1932, with a reunion at the Cafe Royal attended by 300 brethren. However, just as the lodge was rebuilding, the rise of National Socialism in Germany (1933) created a new crisis. Freemasonry was banned in Nazi Germany; lodges were looted, and Masons were sent to concentration camps. Pilgrim Lodge in London transformed from a cultural club into a sanctuary. It became a refuge for men who fled from revolutions, dictatorships and racial persecution.

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 inevitably forced the lodge into a restricted status again. German nationals were classified as enemy aliens. However, the lodge’s role as a beacon of free German culture was more important than ever. The presence of the Norwegian government-in-exile and members of the Norwegian Grand Lodge in London (who had also been suppressed by the Nazis) highlights the broader context of London as a capital of masonic resistance.

The Resurrection Through the Anglo-Foreign Lodges Association (1945-Present)

Following the defeat of Nazism in 1945, Pilgrim Lodge resumed its work with a renewed mission: to build and maintain bridges between people in Britain and in German speaking countries. The lodge became a custodian of the Schroeder Ritual, preserving a tradition that had been nearly extinguished in its homeland.

The lodge continued to play a central role in the Anglo-Foreign Lodges Association. A key tradition involves the Loving Cup, a silver vessel presented by W.Bro. Frank Barnhart of Pilgrim Lodge. This cup is ceremonially passed from the Banner Lodge (the lodge hosting the annual festival) to the next host, symbolizing the unbroken chain of international affection. Pilgrim Lodge remains the senior member, the “primus inter pares” of this international family.

In June 2013, Pilgrim Lodge hosted the AFLA reunion meeting. The Worshipful Master was W.Bro. Douglas Crudeli, an Italian national, demonstrating the lodge’s evolution from a strictly German ethnic enclave to a broader cosmopolitan body working in German. Crudeli performed a double ceremony of the Second Degree in the Schroeder Ritual. The event was attended by the Deputy Grand Master of UGLE and distinguished guests from Germany and Austria.

Today, Pilgrim Lodge No. 238 meets four times a year, on the second Thursday in February, April, October, and December, at Freemasons’ Hall, Great Queen Street. Its membership, numbering around 50, includes men who commute from Germany, Switzerland, and across the UK to attend. The lodge stands as a testament to the resilience of fraternity. It began as a high-degree Christian order for Hanoverian courtiers, transformed into a humanist society for Victorian intellectuals, endured the silence of two world wars, and emerged as a modern, internationalist institution.

Leave a Reply